Understanding different responsible investment approaches

As activity regarding responsible investment (RI) increases, focus points for investors are becoming increasingly diverse. Views on what is ‘responsible’ vary widely and highlight that there’s no ‘one size fits all’ approach. As such, breadth of choice remains important to facilitate the best fit between a client’s needs and product features.

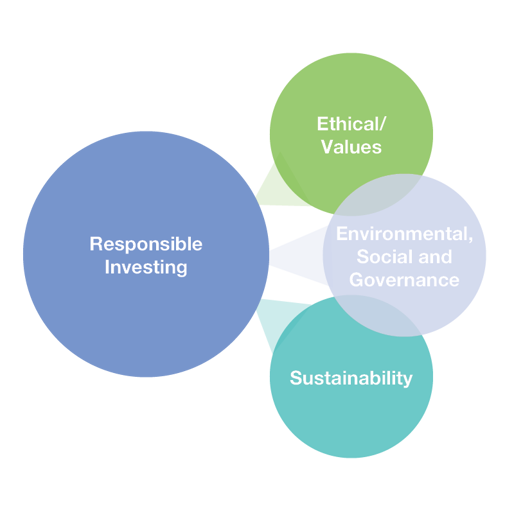

With your RI objectives in mind, there are a wide range of investment strategies from which to choose. At Zenith, we use RI as an umbrella term to encompass three broad categories:

- Ethical investing

- Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) incorporation, and

- Sustainability investing.

While some or all these philosophies can form part of a fund’s approach to RI, we believe they should be viewed as complimentary, but not interchangeable.

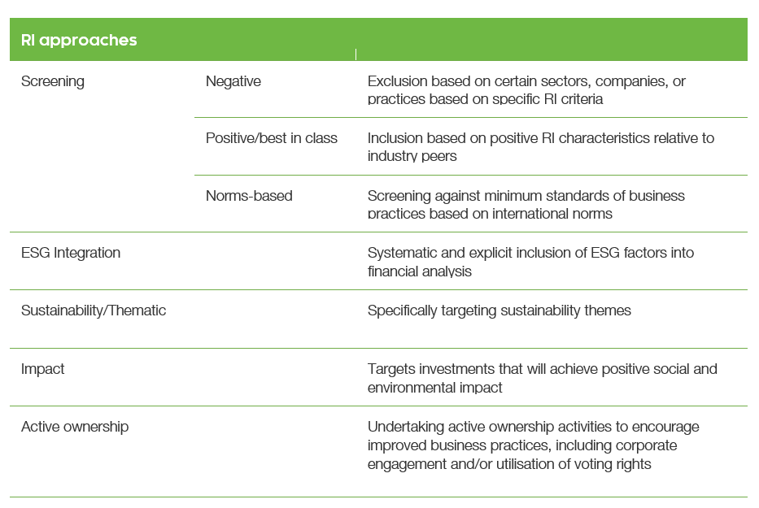

RI can be further broken down into the following major investment implementation approaches:

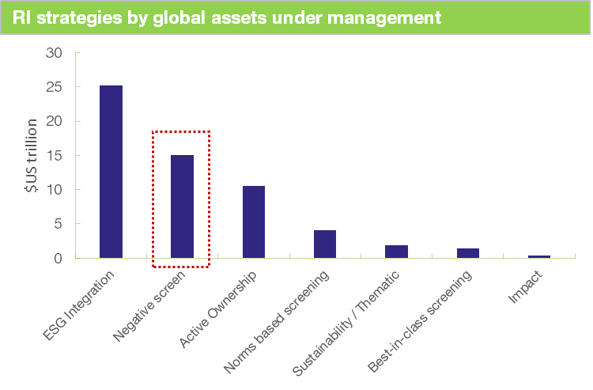

For investors prioritising an ethical or values-based approach, negative screening is the key implementation tool traditionally used. While negative screens are just one of the approaches noted above, acting as a basic tool to which other approaches such as ESG integration or active ownership can be added, it remains one of the most widely-used approaches to implement a responsible investment policy, as the following chart shows.

Source: Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (Aug 2021)

Understanding the fund screening landscape

The use of screening securities for issues or activities is one of the earliest manifestations of RI and has often been used in faith-based investing by avoiding companies involved in activities seen as incompatible with a particular set of beliefs or values.

Many investors apply exclusions to restrict exposure to certain sectors or securities that conflict with their views. Exclusions typically take the form of sectors or industries commonly known as ‘sin sectors’, including tobacco, adult entertainment, gaming and alcohol.

However, while the use of negative screens can be an efficient way to exclude investments, it’s important to understand that their implementation can be highly nuanced, given there’s often no ‘right’ answer in screened definitions.

In addition, while negative screening is often a key feature of funds that specifically target RI objectives, not all funds that use screens actively seek to position themselves as ‘ethical’ or have RI at the centre of their investment process. As such, looking at the prevalence of screening can be useful in uncovering not just funds that prioritise RI, but those simply incorporating screens based on wider mandate restrictions.

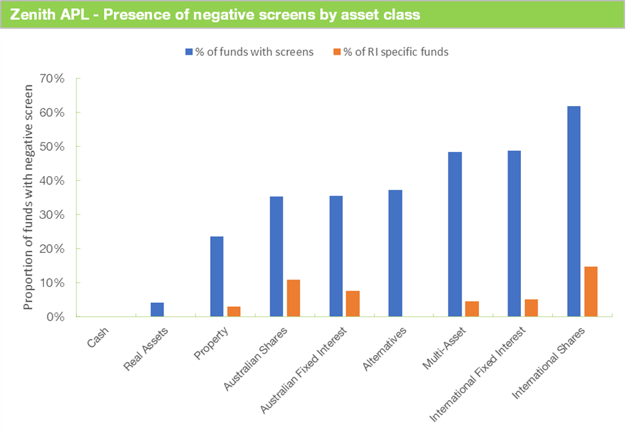

Based on our current Approved Product List, negative screening is widely used. Although funds with a dedicated RI objective make up the minority of available offerings (currently less than 10%), more than 45% of funds utilise formal negative screens.

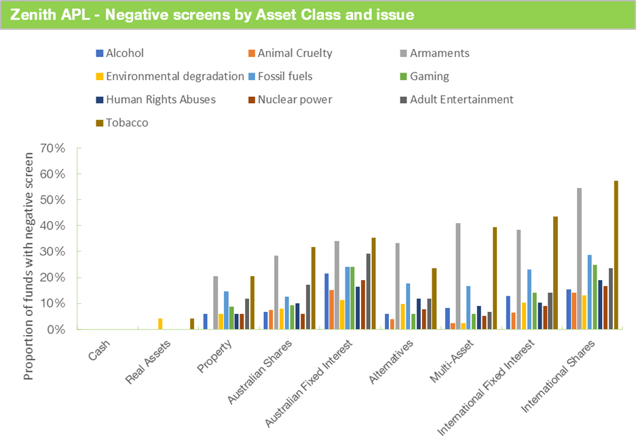

The prevalence of screens across asset classes varies widely, as can be seen in the following chart.

Source: Zenith Investment Partners, Fund Managers

This is logical given the nature of the various asset classes that may not lend themselves to traditional screening issues.

However, it also highlights that the mandating of negative screens by managers is not limited to those funds seeking to formally pursue responsible investment objectives. In the above chart you can see the low proportion of funds considered RI centric and the relatively higher proportion of funds utilising negative screens.

This can also be seen when assessing the proportion of funds that use negative screens as part of a responsible investment approach. Our Responsible Investment Classifications are a guide to understanding to what extent funds incorporate RI and, while it’s evident that screening is most prominent in funds with high levels of ESG incorporation, it’s far from a standard approach. This is logical when considering that many funds view alternative strategies such as impact investing or active ownership as a method of generating greater real-world activity than simply avoiding a sector.

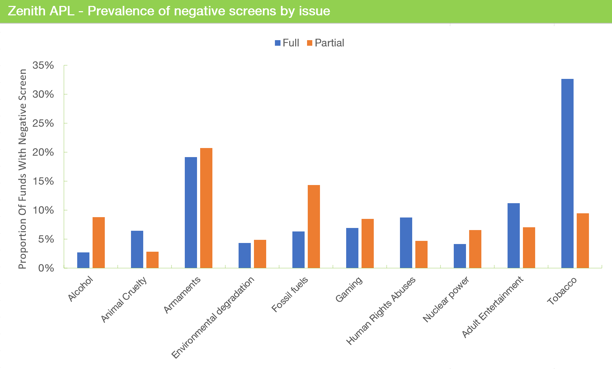

When examining the prevalence of different screens, the traditional ‘sin sectors’ remain predominant, with a particular focus on tobacco and armaments. However, when separated into hard exclusion screens (‘Full’) or screens that are subject to threshold tests (‘Partial’), wide variations in approaches emerge, as illustrated below.

Source: Zenith Investment Partners, Fund Managers

Opinions vary – what should investors consider?

Given the nuances of individual fund mandates, two critical issues should be considered.

Firstly, threshold parameters that apply to ‘partial’ exposures vary widely, so attention should be given to individual fund documentation regarding each fund’s approach to these issues.

Secondly, the extent to which managers consider company exposures to screened issues on a direct basis as opposed to within the value chain is highly variable. As such, assessments of screening could generally be used as an indicator to filter funds for further investigation rather than assuming that screening will fully reflect individual preferences.

When examining screens based on issues within asset classes, several observations can be made. Firstly, the presence of negative screens may not reflect materiality within the asset class. For example, while tobacco and armaments are common screens in Australian equities (as shown in the following chart), there are no companies within the S&P/ASX 300 Index involved in these practices. Similarly, global companies involved in these activities make up less than 1% of the market in aggregate (using the MSCI World ex Australia Index as a proxy for the global market). So, are screens truly active tools, or are they merely ‘hopeful’?

Source: Zenith Investment Partners, Fund Managers

It’s not uncommon for screens to be applied at a firmwide level as a requirement of holding institutional mandates or as a firm-wide view on investability. In addition, given that company activities are not a consideration in broad market indices or as a listing requirement in public markets, the presence of set screens can work to preclude future exposures to ‘sin’ sectors.

While the overt impact of some screens can be marginal, this should not detract from the validity of investors’ ethical principles. However, it does pay to understand that the presence of screens may not necessarily meaningfully alter the investment universe. Similarly, they may not always materially impact returns over the longer term. Conversely, while the long-term performance impact of screens is typically minimal, different screens can exhibit greater performance dispersion relative to broader indices in different markets.

Ultimately, while the simplicity of exclusions means that they’re often widely used, the extent of exclusions may carry various implications for a portfolio. Advisers and investors should consider:

- How does choice of screens change the size of the investable universe?

- Do screens consider exposure solely at the company level, or also within its value chain?

- Are screens normative (universally utilised like tobacco) or more idiosyncratic?

- What implications do exclusions have on the portfolio’s exposure and sectoral biases?

- What are the outcomes for the portfolio’s investment style? Is the portfolio more cyclical or more defensive?

- Do screens change the return profile, such as level of income versus total returns?

- Do the screens create an unacceptable level of tracking error relative to the broader market for the investor?

It should be recognised that while screening can serve a valuable purpose for values-based investors, they can pose difficulties for the broader investor market. For example, a fund’s screening criteria is unlikely to accommodate all investor preferences perfectly. This in turn creates challenges for fund managers during product creation and investor attraction.

Also, while opposition to certain business practices on ethical grounds and investor unwillingness to benefit financially from such activities remain the key drivers of negative screens, this is not the only concern for many investors. Divestment as a change agent in business practices may have limited effectiveness within the timeframes sought by investors, and little real-world impact. Some investors may prefer instead to rely on fund managers engaging with companies and/or impact strategies to transition away from undesirable activities.

For more information about our new negative screen tool, login to Mosaic today.