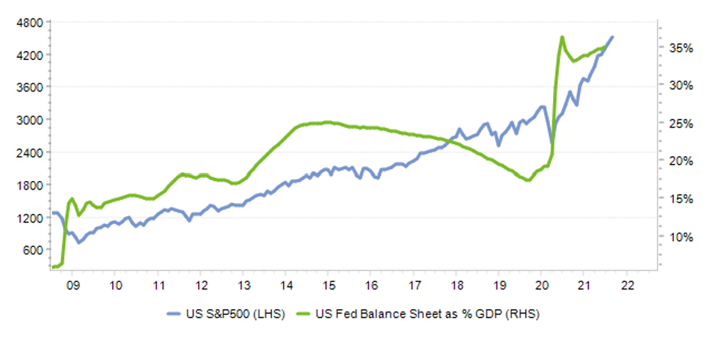

The last 18-months has been unparalleled in many ways, not least because global stock markets have ripped higher whilst the real economy has grappled with a global pandemic. This growing disconnect between an economy placed in suspended animation and continued market gains is partly explained through the liquidity tsunami created by central banks.

Logic would ordinarily dictate that large swathes of the population under virtual house-arrest and the decline in consumption that follows, would see share markets in free-fall. However, central banks, both domestically and abroad, have been countering these forces through unprecedented interventions in fixed income markets.

Central banks gone wild

Central banks have been dutifully mopping up bonds through quantitative easing in efforts to reduce interest rates - as bond prices and yields move inversely. This is due to the stimulatory effect that low interest rates impart through reduced borrowing costs for individuals, governments and businesses which encourages investment and spending, and ultimately, lowers unemployment.

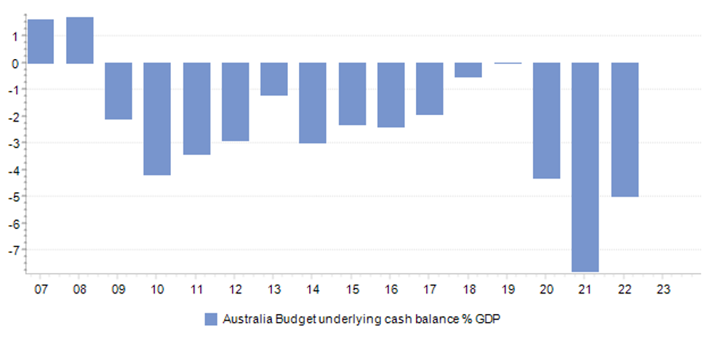

These historically low borrowing costs have facilitated war-time levels of debt accumulation through stimulus programmes such as JobKeeper – now, ‘COVID-19 Disaster Payments’. This is important as increased fiscal expenditure is occurring in tandem with deteriorating tax revenues as fewer people are employed which hinders income tax collection.

Similarly, businesses are generating lower profits which means less government funds from corporate tax payments. Consequently, federal and state governments can provide fiscal support knowing that the RBA will purchase their bonds, and in effect, lend them cheap money – a process replicated abroad, too.

Australian Budget ‘%’ of GDP

Source: Australian Treasury, Heuristics

This extraordinary injection of liquidity into the financial system has been incredibly effective at both suppressing interest rates and bolstering asset values, as the newly created money flows into financial assets. Quantitative easing also indirectly inflates asset values as investors abandon the traditionally safe investments (e.g. bonds and cash) due to the paltry yields on offer.

Bad news is good news

Investors are instead forced into ‘riskier’ investments in search of more meaningful returns. This explains why over the course of the pandemic we’ve seen record-setting returns across property, shares, and even Bitcoin. Similarly, it has created a perverse situation where bad economic news equals good news for markets as investors factor in increased stimulus and liquidity support.

Of course, the ever-present danger is that inflationary pressures emerge in response to a protracted period of ultra-expansionary monetary policy, which forces central banks to remove the punchbowl. Notably though, central banks have been emphatic in their guidance that any inflationary pressures will be transitory, and any eventual unwinding of emergency stimulus will be conducted in an orderly fashion.

This highlights the importance of the forward guidance provided by central banks to steer market expectations of future stimulus withdrawal to circumvent a ‘taper-tantrum’. The RBA demonstrated this in their July meeting through the announcement of a modest taper from September with bond purchases to reduce from $5b a week to $4b. Although this announcement was prior to the lockdowns occurring in NSW and Victoria, the RBA recently reaffirmed this decision despite the associated economic deterioration that’s ensued.

US S&P 500 & US Fed Balance Sheet

Source: BEA, St Louis Fed, S&P, Heuristics

The holy grail

The RBA remains steadfast in its messaging that the preconditions for an official interest rate increase won’t be met prior to 2024. This messaging reflects the constant balancing act between the nascent inflationary impulses permeating society and maintaining financial market stability.

We know, however, that central banks will tolerate higher levels of inflation to ensure the economic expansion is sustained. This has been illustrated through the RBA shifting from forecasting to ‘nowcasting’, in that the board wants to see inflation sustainably within the 2-3% range before an interest rate hike is triggered. The US Federal Reserve has likewise outlined a shift from inflation targeting to ‘average inflation’ – a move that could see inflation overshoot to the upside before monetary conditions are tightened.

In the absence of an abrupt deterioration in the near-term economic outlook, these highly accommodative settings will likely continue to provide fuel for a market rally. Importantly, this moral hazard bears close watching, as the risk of an external shock unexpectedly derailing investors’ portfolios increases.

Participate and protect

With central banks engaged in a high-wire act between blowing asset bubbles and a policy misstep, we maintain our advocacy for active management in our portfolios to help shield against these growing uncertainties. As some recalibration of the pandemic emergency asset purchasing programmes appear inevitable, the risk is that this translates to constrained returns in the near-term.

Partly offsetting these concerns has been the optimistic rebound in earnings observed in the recovery, as we’ve seen investors showered with pandemic profits amid the ‘dividend bonanza’. However, whilst the earnings trajectory highlights a bullish trend, there will come a time when monetary policy ceases to backstop equity markets and the valuation discipline our active managers exemplify will be rewarded.

Therefore, irrespective of the broader market ructions at play, our emphasis on risk-controlled returns for our clients will always take priority as we participate and protect whilst traversing The Wild West of Central Banking.